Anina MathivannanLivestreamed Goodbyes and the Tragicomic Lens of Ethnography

I have never attended a Tamil funeral without a camera present. It always felt ordinary to me: uncles discreetly snapping photos, relatives abroad asking for videos. But as I grew older, and especially during my recent fieldwork, I realized that phones and other digital devices had become central to mourning in the Tamil community. As a researcher I found myself caught between documenting and questioning this practice.

I remember a panel discussion on the topic of “Death in a Foreign Land” that I had moderated during my research period, independently of the research project. One of the panel guests was a Hindu Tamil priest practicing in Switzerland. He recounted how, during the Covid-19 pandemic, he was asked by a woman in Sweden to perform the farewell rituals for her deceased mother. Unable to travel, he set up his laptop in a room above the temple and conducted a three-hour ceremony via Zoom. He explained step by step what family members needed, chanting mantras from his end of the screen. “It was a great challenge for me,” he admitted, “but in that situation, we had no other options.” A digital connection had allowed a ritual to take place at all and the voice of the priest became the thread holding a dispersed family together.

This digital thread was also present in the stories of my peers. Anu and Abi, siblings, told me about watching their uncle’s funeral via livestream: “We just couldn’t be there on site,” Anu said. Abi added, “It helps with grieving, yes, but I wouldn’t want to be filmed in my coffin. You’ve got an audio record of my wishes now, okay?” Their exchange was followed by laughter, but the ambivalence was clear. The livestream allowed participation while simultaneously raising discomfort about exposure and dignity: was this rather a performance than a farewell?

I recognized myself in their tension. When I went to a funeral of a family friend shortly after my research period had begun, and without having planned it (this addition sounds like a poor excuse – about as absurd and ironic as many moments in interviews in this research project), I also took a photo. For my father, who was in Canada at the time. By the next funeral, I took a photo for my sister, who was abroad and close to the deceased. These images remain on my phone; I have never looked at them again. They feel too heavy, yet also too necessary. But I still wonder: was I preserving memory or intruding on grief?

These experiences pushed me to confront my own shock at how casually cameras are used at funerals. Phones appear with an ease that can feel almost traumatizing to those unfamiliar with it. On my Instagram feed, I regularly stumble upon Tamil obituaries: black screens with dates, portraits of the deceased, reposted stories of condolence, and sometimes even videos of funerals. Some of my interlocutors dismissed them as superficial, while others emphasized their importance for connection across distances. For me, they symbolized the way mourning itself has become hybrid – somewhere between private and public, intimate and broadcasted.

Doing ethnography on grief in my own community was never neutral. I carried multiple roles: researcher, mourner, translator, relative. My methods - semi-structured interviews, multilingual transcripts, participant observation - were shaped by strong ethical concerns. Transcribing conversations across Tamil, Swiss German, High German, and English was painstaking, but it allowed voices to remain in their original rhythm. I avoided hidden note-taking, chose not to record certain moments, and sometimes withheld details from my fieldnotes altogether. Even when they would have been valuable “data.” Doing ethnography in my own community demanded responsibility that was both personal and academic.

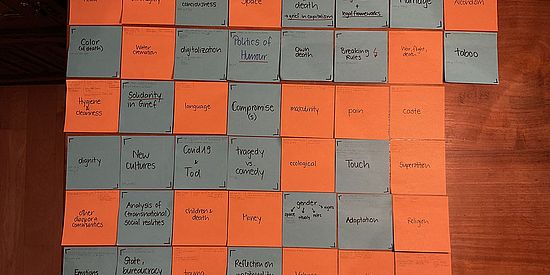

For months, I felt overwhelmed by the contradictions in my material. I organized notes into categories - “legal tragedy”, “digital tragedy”, “social tragedy” – but it all felt incomplete. The breakthrough came when I showed my fieldnotes to Nesi, an interlocutor. As she read, she laughed and teared up, pointing out how sorrow and humor were always intertwined. Her reaction helped me articulate what I had felt all along: that these stories were tragicomic.

Tragicomedy became my way of making sense of livestreamed mourning. A priest chanting into Zoom was at once heartbreaking and absurd. Friends joking about not wanting to be filmed in their coffin revealed both pain and irony. Even at funerals, there was laughter – over memories, over mistakes, over the surreal act of watching a loved one buried through a phone screen. This did not diminish grief. On the contrary.

Looking back, the tragicomic lens taught me two things. First, that diasporic mourning cannot be understood in a single tone. It is solemn and awkward, connective and alienating, dignified and disruptive – all at once. Second, that ethnography is not only about collecting data but about learning to sit with ambiguity. We do not need to resolve contradictions to respect them. No matter whether mourning via What’s App or Youtube is authentic or not, successful or not, it is real. By embracing the tragicomic, I could honor the complexity of this reality of my interlocutors’ experiences and my own.

Perhaps this is the essence of mourning in diaspora: to live with contradiction? To hold a phone at a funeral and feel both dutiful and uneasy. To laugh in the middle of tears. To chant across a screen and believe that presence can stretch beyond distance. For me, this research was less about resolving these tensions than about acknowledging them. And in that acknowledgment, I found not clarity, but truth.

Author Bio

Anina Mathivannan accomplished a BA in International Relations from the University of Geneva and is in her 5th semester of the Changing Societies Master’s Degree Program at the University of Basel. As a second-generation Tamil of so-called Sri Lankan origin who was born and raised in Switzerland, her research interests lay in diaspora studies, peace and conflict studies, human rights, education and the Tamil language, culture(s) and communities. She currently works at the intersection of human rights and education.

Context

This text grows out of the two-semester ethnographic fieldwork for the course "Living Together, Apart: Transnational Attachments, Intimacies, and Kinship” (Autumn 2023/Fall 2024, Dr. Michelle Engeler). Anina Mathivannan focused on second-generation Tamils in Switzerland and combined semi-structured interviews, conversations, participant observation, and autoethnography. Multilingual transcription (Swiss German, High German, Tamil, English) and strong ethical questions on how to conduct ethnographic research were central to the process. The work sits at the intersection of diaspora studies and thanatology (death studies), asking how grief is practiced, mediated, and negotiated across families, laws, and distances.

Quick Links

Social Media